Since man first stood upright on this planet he has been a creature like none other. In his earliest days, he was a hunter-gatherer. That meant he used very rudimentary tools to kill animals and he harvested fruits, berries, roots, and other edible plants to stay alive. To be sure, for man’s first million years, his was a constant struggle just to stay alive.

But during this period he also started to move outward from East Africa where he first rose to prominence. He discovered that even though he was not match for many of the larger animals he co-existed with, he could use his brain to elude those animals should they decide they had a taste for human flesh.

But also during this period man discovered war. Man grew from family groups into small protective groups and then into small communities. These communities fought one another when food became scarce and possibly when one group felt another was impinging on their territory. This probably did not happen very much but we need only look at today’s society to discover man’s ancient proclivities.

And so it went until the 20th Century arrived. The 20th Century, and now the 21st Century, have burdened our planet early like never before. Even though the industrialization of the Earth started in the 19th Century, those toxic fumes emitted by mills were not so great that they posed an immediate threat to Earth’s biosphere.

The 20th Century, however, was one of great scientific and industrial invention. It has also been the period of the most rapid growth of Earth’s human population. Between these two things, planet Earth has been put at risk of dying, literally.

Industrialists, and those who support them, contend that what is happening to planet earth is little more than a natural progression. That the earth is warming is nothing new and those who complain about it are just alarmists. The contend that there is more than enough proof that the Earth has gone through similar events and survived. The question here is: Is their logic sound?

During the 1940s through and into the 1970, aerosol cans used a gas named florochlorohydrocarbons. This gas was used in items such as hair spray and other consumer items that needed a gas to propel their active ingredients. When it was discovered that the use of this gas compound was causing a big hole over the Earth’s poles where ozone had previously existed, the federal government stepped in and banned the use of those compounds. Most other countries on the earth did the same, following our lead. The result was the holes closed up and there was proof positive that man had caused an unnatural imbalance in the earth’s biosphere.

Plastic was first made in the 1920 but did not come into any sort of widespread use until the 1950s. As a child I remember our milk was delivered either in glass containers or paper containers that were lined with was. Neither of these containers posed any threat to our biosphere. Additionally, most other liquid items were delivered either in glass or metal containers. Again, no serious threat to the biosphere. But starting in the 1970s industrial economies dictated that the delivery of fluids in plastic containers was much more economical. Glass containers, such as the soft drink industry used, required that the bottles be returned, then cleaned for reuse. This process proved relatively expensive. Today, such a process is considered “green.”

Grocery stores changed over from the paper bag to the plastic bag. Plastic bags were less expensive and required smaller spaces for containment. But plastic bags, once recycling took hold, were not acceptable items for many communities recycling. The problem? They tended to get bound up in the gears of the machinery processing them with the other forms of plastic and therefor became prohibited items.

Curiously, one of the nation’s larger food market chains which uses only paper bags and promotes its reusable repurposed plastic bags has no system to capture used plastic bags. To be fair, the reusable plastic bags that I am referring to, feel like fabric to the touch and last a long time making the need to use a food stores plastic bags unnecessary. This is an industry at least attempting to take positive measures in the responsible use of plastics.

To further illustrate the threat these plastic containers pose to the planet, there is an island of plastic sitting in the middle of the oceans larger than 3 countries. More, who has not been to a beach where plastic bottles and bags could be found along the beach front?

The other great threat to our biosphere is atmospheric pollution, green house gases. Most prominent, but not alone, are carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO2). I put the chemical formula for these compounds to show how closely related they are. Carbon monoxide is unstable and will capture an oxygen molecule quickly thereby robbing our atmosphere of its precious oxygen content and leaving behind carbon dioxide, the compound which most seriously impacts the green house warming our planet is presently experiencing. Green house gases trap sunlight in the earth’s atmosphere, sunlight that would otherwise be reflected back out into space.

One method scientists use for tracking the effect of our planet’s warming is the regression of glaciers. In the 1930, many was the author who wrote about the snows of Mount Kilimanjaro in Africa. They were legendary but they no longer exist because of global warming. Of particular interest to them has been the glacier which covers most of Greenland. This glacier has always melted during the summer months but the rate of melting has increased over the past decades. Also, where small puddles of water that existed atop this glacier during the summer months, they have been replaced by large lakes, further proof of the extent of global warming.

One of the side effects of global warming, and probably the most deadly to the continued existence of the human race, is that deserts are becoming larger and small tracts of arid land are fast converting into deserts due to the lack of rainfall. The reason for the lack of rainfall is how air circulates around our planet. The rainy seasons that sub-Saharan residents used to rely upon have all but disappeared. The Sahara desert in turn moves southward pushing out the people who used to populate this land. Many other parts of our planet are experience elongated droughts. Such droughts have never been recorded in these areas for as long as man has inhabited them.

A case in point is California. California had traditionally relied upon the snows of the Sierra Mountains to provide them with needed water. But for years on end the snows came in such reduced amounts that the reservoirs they typically filled fell far short of the water necessary. Certain of these reservoirs dried up completely. The city of Los Angeles was in crisis. The drought ended just in time to avert the crisis at hand. But it is only a question time, and not an if, when the next elongated drought strikes the southwestern United States and it lasts far longer than the available water can support.

California is one of the chief vegetable and other food producing areas of the United States. A plant killing drought will be disastrous for both the people of the United States and its economy. That a single state can be the root of a catastrophe illustrates how dependent we are on any one region being economically healthy.

The bottom line is: the Earth is reliant up a series of interrelated eco-systems, each reliant upon the other. When any one of these systems changes, even slightly, the effect of that change is felt in all the rest of the systems. The question is how much is each system affected? That we can quantify the rise in the temperature of sea water to be several degrees is hugely significant. Were it just a tenth or two, there would be no reason for concern. But that is simply not what is happening. The larger question at hand here is: how much more will the temperature of the oceans rise? The is extremely important because the ocean’s temperature directly affects weather patterns. In the Atlantic ocean we have seen a marked increase in both the number and the intensity of hurricanes. In other parts of the earth the change in weather patterns have caused stronger winter storms, greater flooding, hotter summers and even colder winters.

That the United States has withdrawn from the Paris Climate Accords is a travesty. It says that the United States cares more about corporate profits than the continued life of our planet. The United States, which for over 100 years, has lead the world in most areas, has abdicated its leadership responsibility. This is a debt which must be paid whether the United State’s present political leadership acknowledges or not. The debt grows daily and will be paid by our children, our grandchildren, and our great grandchildren.

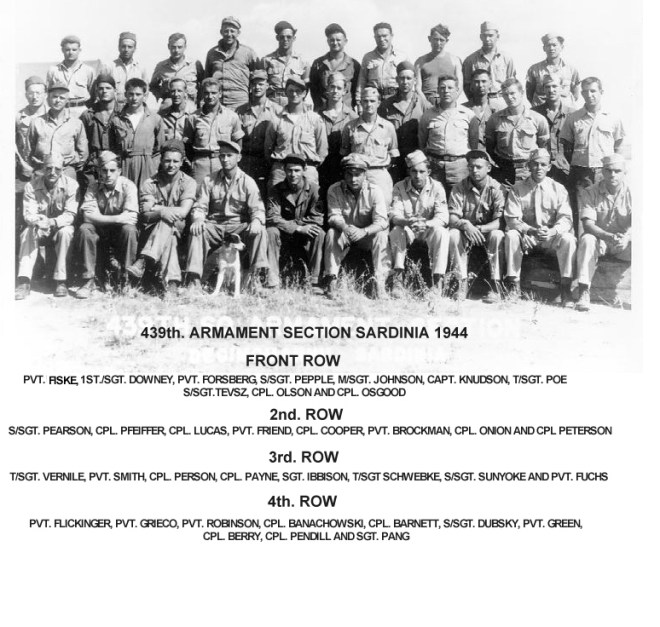

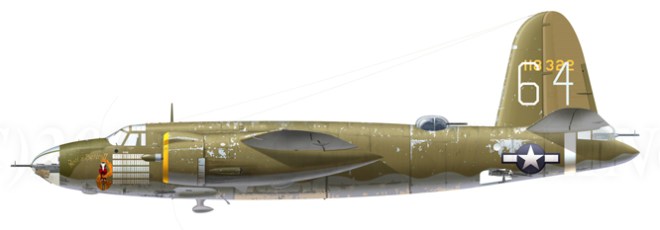

What follows is an exact copy of a report written during World War 2 by a SSG Robert A. Wade commemorating the 100th mission of the B-26 bomber “Hell’s Belle.” I have transcribed it exactly as it was written.

What follows is an exact copy of a report written during World War 2 by a SSG Robert A. Wade commemorating the 100th mission of the B-26 bomber “Hell’s Belle.” I have transcribed it exactly as it was written.