By the first of March, the 7th week of the strike, it seemed as if the strike would go on forever. Neither side had flinched and no progress was made at any of the meetings held in Boston. But one thing had changed, the federal government became involved. On March 2 the U.S. House Committee on Rules convened a special session to hear testimony about the strike. The mill owners were represented, the unions were represented, and the strikers were represented by about a dozen operatives who had traveled to Washington to give testimony before the committee. The committee was headed by Rep. Robert L. Henry, Democrat from Texas. The committee had nine members in all plus a clerk.

Also on March 1st the mill owners, probably seeing trouble ahead with the federal government’s involvement, offered the strikers a 5% raise. But they were not willing to give in on any of the other strikers’ demands, particularly on the premium system which William Wood characterized as being “all right” just like it was. This was Wood’s response to IWW strike committee member Annie Welzenbach, the only woman on the committee. Ms. Welzenbach responded, “No Mr. Wood, we know that the premium is all wrong.” (“I.W.W. Strikers Firm,” (Lawrence) Evening Tribune, March 2, 1912) The owner of the Brightwood Mill in North Andover whose operatives were not striking, announced on March 4 that he was giving his workers a pay raise immediately. Similar raises soon followed in the mills of New Bedford, another city with many thousands of textile workers. The raises were generally around 5%.

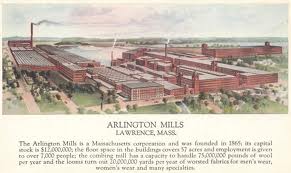

In an attempt to sabotage the strike, the Wood Mill and the Arlington Mill announced 5% pay raises for any operatives who returned to work.

During the month of February, the AFL had given some assistance to the strikers but on March 4th announced it was withdrawing its assistance as it once again took an anti—strike stance.

What follows are excerpts from the U.S. House Rules Committee hearings held from March 2 – 7, 1912. (House of Representatives, 62nd Congress, 2nd Session, Document No. 671 – The Strike At Lawrence, Mass. – Hearings Before The Committee on Rules of the House of Representatives on House Resolutions 409 and 433)

“Statement of Hon. William B. Wilson, A Representative in Congress from the State of Pennsylvania: ‘Mr. Chairman, a few days ago the entire country was startled by the story . . . [that] the police powers of the State of Massachusetts . . . were being used to forcibly prevent the children of strikers from being sent out of the city . . . [to] where homes had been provided for them . . . so far as I know, there has never occurred in the history of trade disputes . . . any conditions approaching or even approximating the conditions which are alleged to exist at Lawrence . . . there is hunger and suffering on the part of those who are making the contest . . . and [they] feel that their children would be better provided for . . . by sending them to the homes of others . . . In my judgment it is the height of cruelty to prevent them from sending these children to such places . . . [and] there should be no power on the part of any State to prevents the parents from sending their children . . . so long as they are not deserting these children . . . ‘”

At this point a long series of resolutions from cities and states from around the U.S. are read into the record. Each resolution is a condemnation of the treatment of the strikes and a number of resolutions asking Congress to send monetary aid to the strikers, among other things.

During the afternoon session the committee heard the testimony of Samuel Lipson, a skilled worker from Lawrence who worked in the Wood Mill. He was questioned by Rep. Victor Berger of Wisconsin, a socialist. Lipson was queried about his pay, his hours and the regularity of his work. Then he was asked by Rep. Berger:

Berger: “Were the strikers clubbed (by the police)?

Lipson: “[yes but] it always happened that the police started the trouble.”

Berger: “In other words, it was sufficient to be a striker in order to be a criminal in the eyes of the police of Lawrence?”

Lipson: “Yes sir.”

Berger: “That was the crime?”

Lipson: “Yes; and that is why the trouble always starts, you know.”

Berger: “Now, just tell me, do you know the name of the woman that was killed?”

Lipson: “Anna Lapizzo.”

Berger: “Who killed her?”

Lipson: “I will tell you . . . our witness swore (at the Ettor trial) that they saw the policeman, Benoit, fire from his revolver and the shot that killed the woman. . .”

(Later in his testimony)

Lipson: “And some other ministers tried to speak to their people against the strike, saying if the did not return to work they would never be in heaven . . .”

Berger: “No ministers on your side?”

Lipson: “No.”

(still later)

Berger: “[in court] You mean the striker does not get credence? His evidence is not believed in court?”

What follows is the testimony of John Boldelar, age 14, of Lawrence.

Rep. Campbell: “How many rooms are in your house?”

Boldelar: “Three.”

Campbell: “How many stoves?”

Boldelar: “One.”

Rep. Wilson: “What furniture have you in the house?”

Boldelar: “A couple of beds, that is all.”

Rep. Pou: “I have heard quite a number of people living on bread and water. Has there ever been a time when you were compelled to live on bread and water?”

Boldelar: “Yes, sir. . . sometimes we did not have enough money to buy bread one or two days.”

What follows is the testimony of Tony Bruno, 15 years old, of Lawrence.

The Chairman: “What is the smallest pay you ever get?”

Bruno: “About $1.”

Chairman: “$1 a week?”

Bruno: “About $4.”

What follows is the testimony of Camella Teoli, 14 years old, of Lawrence. Her testimony is considered some of the most compelling of the entire hearing. As with the others she is queried about the size of her family and the pay and conditions of her family.

The Chairman: “Now, how did you get hurt, and where were you hurt in the head; explain that to the committee?”

Teoli: “I got hurt in Washington.”

Chairman: “In the Washington Mill?”

Teoli: “Yes, sir.”

Chairman: “What part of your head . . . how were you hurt?”

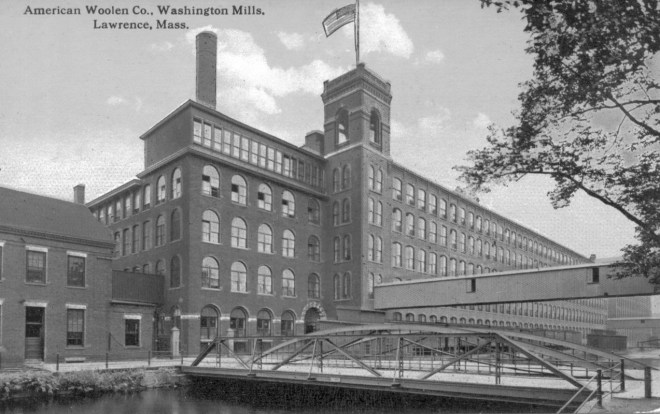

Teoli: “The machine pulled the scalp off.”

Chairman: “The machine pulled your scalp off?”

Teoli: “Yes, sir.”

Chairman: “Were you in the hospital after that?”

Teoli: “I was in the hospital seven months.”

Chairman: Did the company pay your bills while you were in the hospital?

Teoli: “Yes, sir. . . the company only paid my bills; they did not give me anything else. ”

Chairman: “They only paid your hospital bills; they did not give you any pay?”

Teoli: “No, sir.”

Teoli testified later that her father had been arrested because he had gotten papers saying she was 14 when she was actually 13. This was found to be rather common practice however.

It became increasingly clear to everyone in Lawrence, and the nation, that the strike needed to be settled in favor of the strikers. Sentiment was no long on the side of the mill owners and they knew it.

William M. Wood, of the American Woolen Company, came to feel the wrath of the committee when it, the committee, decided that a special committee be formed to specifically investigate the American Woolen Company which he owned and was the president. The committee very pointedly stated that the American Woolen Company had benefited greatly from the U.S. Government’s purchases from it, in particular the U.S. Army. But additionally, the committee was told to investigate any trusts that had been formed, they were illegal, investigate excessive capitalization, fictitious capitalization, stock speculation and conspiracies, and its controlling the price of labor. Wood no longer had anywhere to hide, nor did the several owners of the other Lawrence mills.

On March 13, 1912 a settlement between the mill owners and the strike committee was reached. And on March 14, 1912, the strikers voted to end their walkout. What follows is the concessions won by the strikers:

- All people on job work, 5% increase flat

- All those receiving less than 9 ½ cent an hour, an increase of 2 cents an hour

- All those receiving between 9 ½ and 10 cents an hour, an increase of 1 ¾ cents

- All those receiving between 10 and 12 cents an hour, an increase of 1 ¼ cents per hour

- All those receiving between 12 and 20 cents per hour, an increase of 1 cent per hour

- No discrimination will be shown anyone

(“Accept Wage Increase,” (Lawrence) Evening Tribune, March 13, 1912.

The one concession the strikers were unable to get was elimination of the premium system. The mill owners did agree, however, to pay the premium even two weeks instead of every four.

A few years later the strikers realized they had settled for far less than they could have gotten had they held out for all their demands, particularly the 15% pay raise and elimination of the premium system. For decades following the strike many felt shame over what might have been and chose to not speak of the strike. For that reason, there is precious little verbal history on the strike. Most of what we know from the striker’s position comes from the U.S. House’s investigation and what the newspaper reporters wrote.

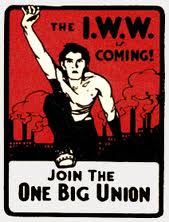

But the Lawrence strike helped invigorate unions all over the United States. A few months after the Lawrence Strike ended the operatives of the Paterson, NJ mills went on strike for much the same reason. The IWW faded from the American landscape after 1912 as the AFL finally accepted unskilled labor into its ranks. The Knights of Labor, led by Samuel Gompers, had no part in the strike, but Gompers himself showed up at the committee hearing and gave a mildly favorable nod to the strikers. The Knights died out completely shortly thereafter.

To its credit, the IWW had led the way in how to conduct a successful strike. It had engineered the first sit down strike in Rochester NY which ended successfully. And then its inclusiveness at Lawrence empowered the non-socialist unions around the United States giving rise to unions such as the teamsters, mineworkers, steelworkers and dock workers. Each took the IWW’s lead in conducting their strikes and turned their former poor record of winning around.

The Lawrence Textile Strike did not become known as the Bread and Roses strike until some time after its end. It gained that moniker via a protest song of the same name which was sung by the strikers in Lawrence during their ordeal.

As for Ettor and Giovannitti, as I said earlier they were held over for trial in Salem. When the trial commenced in October 1912, it was obvious the men were guilty of nothing and were soon set free.

The Lawrence Police Department, the Massachusetts Militia, the mill owners, none received even a rebuke as a result of the strike.