All strikes have leaders. These leaders are generally union leadership. They have meetings at which the union membership takes a strike vote, yea or nay. In Lawrence, however, the strike which started on January 11 1912 was the very essence of a “wild cat” strike. There was no vote taken, no large membership discussions of how a strike should start and then proceed. It simply started by the action of a few Polish women in one mill who in turn enticed those who worked beside them and those who worked in other mills to join the new strike.

Not everyone got paid on January 11 and so there was reticence among the operatives of mills which had yet to pay their employees. They held out hope that they would not meet the same fate. But when Friday dawned and those operatives were paid, it became crystal clear that the management of all the mills had colluded and reduced everyone’s wages accordingly.

But as I was saying, every strike has leaders and this one was no different. The I.W.W. had in place already a dozen men in leadership positions as representatives to the various ethnic groups. And so on January 12, 1912, Angelo Rocco, one of the IWW’s Lawrence leadership, sent a telegram to the IWW’s New York offices informing them of the strike’s beginning and requesting immediate help. The next day a squat young man named Joseph Ettor, along with his friend, Arturo Giovannitti, arrived in Lawrence to represent the IWW’s headquarters. Ettor’s boyish looks gave way to his ability to speak in several of the native dialects spoken in Lawrence. A poet by training, Ettor was discovered, or discovered, the IWW in the coffee shops around Washington Square in New York. His demeanor was very disarming, he looked as though a single harsh word might render him speechless. But when he spoke, his words conveyed the fervor of his beliefs in the IWW and what it stood for. Ettor wasted no time upon his arrival in Lawrence and called for a rally in the Lawrence common for the very next day. He recognized that the union must speak its demands with a single strong voice and his plan was to be that voice. And so the IWW was fully involved from the first day of the strike.

Figure 1. Caruso, Ettor, Giovannitti

The AFL, to the contrary, and on the orders of John Golden who was president of the Untied Textile workers in Massachusetts ordered his works to not strike. The AFL felt similarly to the political and industrial leadership of Massachusetts that these unwashed immigrants would soon fold under the pressure of starvation and return to work. They also felt that their membership was reasonable compensated and they therefor had no dog in this fight. What they would find out was that their member did not necessarily agree with that sentiment.

One of the tactics used by mill owners to increase production without incurring additional expenses was to speed up the looms. While this mostly affected the unskilled labor it did also affect the skilled labor when the looms broke down, they were called in, and the looms broken down more often with the increase in speed. But even more basically, they too had to work the 54-hour week, had to endure uncertain working futures as during lean times both skilled and unskilled labor were subject to layoffs. The uncertainty of a steady income was one of the most galling things all operatives faced.

The Boston Sunday Globe reported on January 14 “Mills May Close” and “15,000 Out at Lawrence,” and, “Grave Fears for Tomorrow.” Those grave fears were rumors that the strikers were probably planning riots. To that end, the Major of Lawrence, Scanlon, had requested the state send in the militia to preserve the peace. But the words no one outside the IWW had yet heard was Ettor admonishing his followers to maintain a peaceful strike. He exhorted them to maintain a non-violent attitude even when attacked.

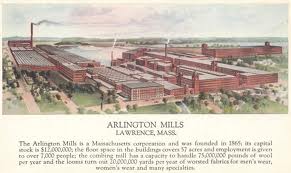

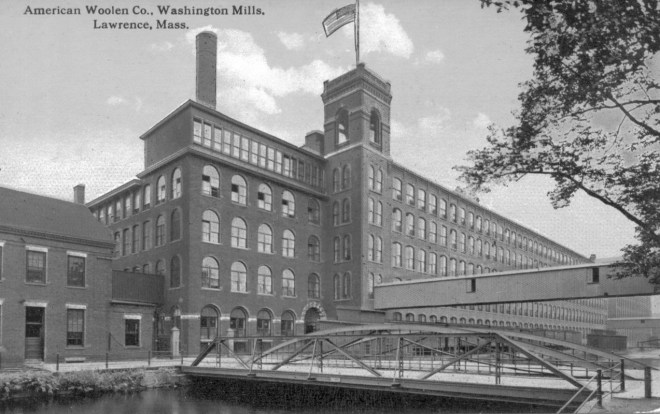

To give you some semblance of the size of these mills I have included pictures from 1912 of four of the 12 mills that were struck.

Figure 2 The Washington Mill on Canal Street

Figure 3 The Wood Mill on Merrimack Street

Figure 4 The Pacific Mills along the Merrimack River

Figure 5 The Everett Mill on Union Street

As can be seen from the pictures these were massive complexes which produced a very large portion of the nation’s woolen, woolen worsted and cotton fabrics and clothing. One of the chief purchasers of their good was the US Government. They had uniforms and blankets made in these mills.

On January 15th three companies of Massachusetts Militia arrived at the Lawrence Armory to assist the police in maintaining the police. The militia was of course an unwanted sight by the strikers. The picture below is a famous depiction of striker vs. militia.

Figure 6 Massachusetts Militia and the strikers stand toe-to-toe

The peace at this point was certainly an uneasy one. But the militia’s commander, a Col. Sweetzer, commanded his troops to approach the gathered crowds with fixed bayonets. This was just one of the many provocations placed in front of the strikers to most like get them to do what they professed they were there to stop, riot.

The picture below shows the militia entering the Everett Mill at the owners request to keep his property safe. There had been acts of vandalism, small acts but still a bit costly.

Figure 7 Militia entering the Everett Mil

Over that first weekend the IWW had formed what was called “the strike committee.” It was comprised of 56 men of all nationalities whose job it was to see the strike through to a successful conclusion.

Then on January 18th, after the strikers had marched up and down the sidewalks of Lawrence’s Essex Street, its main street of commerce, Col. Sweetzer declared that the strikers were breaking the law by inhibiting business on Essex Street. And to be fair, that was part of the IWW plan. But unfazed by Sweetzer’s pronouncement, Ettor told his followers to stay off the sidewalks and march down the streets, as show below.

Figure 8 Solidary March of Striking Operatives as formed by the IWW

These immigrants were certainly very new to America but the understood quite well, as prompted by Ettor, their right to assemble and freely march, and march they did with great frequency. The Lawrence police department felt no sympathy for striking operatives and frequently took out their frustrations on any immigrant who they observed has having even slightly broken a city ordinance. Their form of immediate justice is shown below.

Figure 9 Lawrence police clubbing a lone striker

Then on January 18th Mayor Scanlon declared that if the strikers desired to have further marches they would have to get a permit which he had no intention of issuing. On this point the strikers ignored the mayor and marched anyway. They mayor was helpless to stop the marches.

By Saturday January 20, nearly 20,000 operatives were on strike. Some of these operatives included skilled labor who were AFL union members! The AFL was still a long way off from joining the strikes so this shows how there was an even more general feeling of animosity towards the mill owners.

Then on January 21, the Boston Sunday Globe headline read “Wolf of the Doorsteps of Lawrence Strikers and Terrors of Hunger Facing the Leaders.” But what the Boston Globe, the mill owners, and those external to the strike had failed to realize was the fact that the IWW had already set up soup kitchens and small food banks to see the strikers through their ordeal. This is just one example of the product of the Strike Committee in meeting the challenges it faced.

Still, the strike was little more than a week old and there was still an overwhelming feeling among state leaders and mill owners that the strike would soon fail. The arrogance of the mill owners cannot be overstated. One said that the operatives received a “high average pay” as reported in the January 18 Boston Globe. In truth, the average operative’s wage, and this included skilled labor, average a full 50% lower than in other parts of the state! The high average for an operative was $7.50 per week for a full week’s work and a full week’s work was frequently rare. In my studies I found the average was a lot close to $6 or about 1/3 of what other unskilled laborer in the state received. Considering the average apartment cost the worker $2.50 a week, he had little left for necessities like food, clothing and heat in the winter. Medical care was non-existent and even though all children under the age of 14 were required to attend school, the immigrants could always find a guy who would get the papers showing their children as being older than they actually were. In truth, the average family needed 100% of those able to work working just to keep up. This fact brought out many of the “radicals” of the day. One woman, Mary Heaton Vorse who was at the strike wrote a book called Footnote to Folly in which she described the deplorable conditions the immigrants lived in.

Another person the strike attracted was an IWW man known as William “Big Bill” Haywood. Lawrence leadership feared his arrival and with good reason, where he went trouble seemed to follow. But Haywood was the face of the IWW and his presence was merely to insure the strikers that their needs would be taken care of by the IWW. Haywood only stayed a few days before he lit out on a tour of New England cities and towns where he spoke of the strike in Lawrence and their need for money to feed the striking operatives. At this he excelled and the dollar quickly rolled into the IWW’s strike headquarters in Lawrence.

This would be a great story if it could be said that for the entirety of the 62 days of the strike there were no riots, not disturbances, no hostilities. But only one of those remained true, there were no riots, ever.