What follows is the true story of labor unrest in the city of Lawrence Massachusetts in 1912. In the history of the United States, before or since, this is the largest strike to effect any single city. But out of it came many of the long overdue changes needed for working men and women. The improbability of success for this strike was extremely high and that it would last 62 days was unheard-of. If on January 1 1912 you had asked anyone could a strike not only go on for 62 days but end in success, you would have been roundly laughed at. It was considered impossible, even by labor leaders. But this strike got the attention of the nation, and possibly even more importantly, it got the Republican President of the United States, William Howard Taft, a friend to management, to summon a house committee to investigate the strike while it was in progress!

To tell this story in one sitting is too much. I am breaking it up into many parts and will endeavor to keep both detail and interest high. The protagonist in this story, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), won the day but lost in the long run while the antagonist, the American Federation of Labor, lost the day but won in the long run. And the mill owners, well, they won even in losing as is often the case even today.

Lawrence Massachusetts was born from portions of two other towns, Methuen and Andover. It had been proposed that a showcase manufacturing city be built on the banks of the Merrimack River. Each town gave up a little over 3 square miles of land towards that dream. As a consequence, one more new town was created as Andover split in 1853 into two parts, Andover and North Andover, each having its own government.

The financing came from a group of Boston Bankers who had observed the huge success Lawrence’s sister city, Lowell, had been just 20 years prior. Its mills were large and bustling and bringing a tidy profit to owners and shareholders alike.

By 1900 Lawrence was Lowell’s equal in the manufacture of textiles. And to insure a constant power source, the founders of Lawrence had built a dam on the Merrimack river from which two canals were built to bring water to the new mills. The water was needed for the large steam turbines that powered each of the mills.

It was around 1900 when the make-up of the two cities diverged a bit. Lawrence became a magnet city for large numbers of America’s new immigrant groups, Italians and Poles making up the bulk. But there were also Armenians, Russians, and Syrians. The Italian immigrants are a curious anomaly for Lawrence. While both Lawrence and Lowell were attracting large number of these new immigrants, the vast majority of Italians chose Lawrence over Lowell. I have not been able to discover a reason for this except that it is known that William Wood, president and owner of the American Woolen Company, a conglomerate of over a dozen mills, sent men to Italy where posters were put up claiming that any who wished to emigrate to America would share in its riches. Wood vociferously denied this because to have done so would have broken American law. But there was no shortage of immigrants who claimed to have come to Lawrence because of his posters.

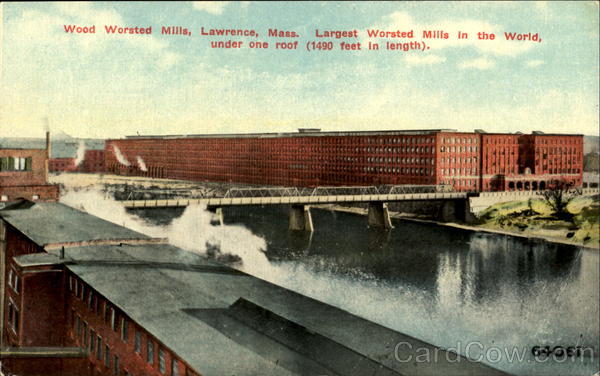

This group of immigrants, starting around 1900, are known as the “new immigrants.” The “old immigrants” included the Irish, Germans, Welch, Belgians, and French Canadians. They had held all the positions in Lawrence mills until 1900. Wood at the time was building two new mills, the Ayer Mill and the Wood Mill. The latter is the largest single mill enclosure ever built in America. But the labor pool available to fill these new mills was quite short hence Wood’s decision to entice new immigrants.

Wood really did not need to entice the Italians; they would have come anyway. The European economy of the early 20th Century was very weak. In southeastern Europe, the Balkans, Greece, and Turkey, the old Ottoman Empire was beginning to crumble but it was not going quietly. It was during this period the Turks declared war on Armenia and set about to obliterate it with one of the worst genocides ever.

In Eastern Europe the Russian Empire was also beginning to fall apart. The Czar had set about ridding Russia of its Jews by a series of Pogroms. The ploy was to unceremoniously push the Jews from where they had been living westward with the idea that they would tire of being constantly uprooted and leave the continent entirely. And to a small degree that worked.

Until 1907 Russia ruled over half of Poland. It was there that Russia pushed many of its Jews. But it also imposed its tyranny on the native Poles by requiring military service from its young men. This, of course, did not sit well with the Polish people and rather than fight the mighty czar, many chose to leave for the New World.

By 1912, Lawrence’s population was close to 90,000, an incredible number considering the city was barely 60 years old. The major of its population was either new immigrant or first generation immigrant. Because of this it gained the nickname “immigrant city.” But unlike other cities that attracted large numbers of immigrants, New York and Chicago, Lawrence was not divided into ethnic neighborhoods. For example, the first block moving away from the large Everett Mill had a large number of Italians and Poles with a few Syrians, French and English mixed in. This is not to say Lawrence had no ethnic neighborhoods, it did. The Germans settled an area known as Prospect Hill. The French and Irish had neighborhoods in South Lawrence. But considering Lawrence had claim to at least 15 large ethnic groups, those exceptions are the outliers.

Social unrest in Lawrence started, at the latest, in 1910. It was, however, part of a greater unrest going on in all of Massachusetts. The average mill worker in 1910 was required to work a 58-hour week, 10 hours a day Monday through Friday and 8 on Saturday. It is important to note that this was true for both skilled and unskilled labor. It was the skilled labor that petitioned for, and was granted, a shorter work week when the Massachusetts legislature passed a law reducing the work week to 56 hours which took effect in 1910. In 1911 it changed that law and reduced the work week to 54 hours starting January 1, 1912. It is that point this story begins.

Prior to 1912 unions nationwide were weak even though a number, but mostly the coal miners, conducted large scale strikes. But strikes seldom ended in a win for the working man. Mill and mine owners alike used the tack of hiring new workers to replace the striking workers. Such moves sometimes resulted in riots as in the Pullman Strike and the Johnstown strike. Lesser strikes were frequent in the western coal fields of Wyoming and Colorado but out of them came a man who would greatly influence the Lawrence strike of 1912. He was known as William “Big Bill” Haywood and he represented first the Western Miners Union and later the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The latter was ill-received by Americans because of its socialist doctrine and its affiliation with known anarchists and other “trouble makers,” as they were called.

Extremely poor working conditions in the textile and garment industry was well-documented. Just a year earlier in New York City, March 1911, a disaster known as the Triangle Shirtwaist fire caused the death of 146 garment workers, mostly women, many who jumped to their death or were burned alive. The factory owner did not want the women sneaking out so he had ordered exit doors chained and locked during normal working hours. Their escape routes blocked, the women had to rely on a small and slow elevator. The fire horrified New Yorkers and reforms were called for, some were even enacted, but state legislatures in those days held little empathy for the average mill worker. The reason being a simple one, their election often times relied upon the largess of the mill owners.

In June of 1911, and possibly foretelling a strike, a member of the I.W.W., probably Joseph Ettor, came to Lawrence with the expressed job of recruiting workers into the IWW. Ettor would play a prominent role later on in the strike. The only other union in Lawrence at the time was the Textile Workers Union, a branch of the larger American Federation of Labor (AFL). The TWU membership was entirely made up of skilled labor as was in keeping with AFL doctrine of the day. But the majority of mill workers fell into the category of unskilled labor. Conversely, the IWW had no such restriction and welcomed all comers, skilled and unskilled, into what it called “one big tent.” But to be a union member you had to pay dues and therein lay the problem for the IWW. The group it most ardently wished to represent could not even afford the meager one dollar dues as the worker was already living on starvation wages where pennies were counted. The total membership of the IWW prior to, during, and after the strike never exceeded 900. There were close to 35,000 mill operatives in Lawrence at the time.

January 11, 1912, a Thursday, the residents of Lawrence awoke to a bone chilling 10-degree morning. For many breakfasted consisted of molasses spread over bread. With the exception of the Arlington Mill, all of Lawrence’s mills were clustered along the Merrimack river and an easy walk for the operatives who filled them. Notwithstanding the literal chill in the air, there was also a great deal of tension. On that day the first pay envelopes of the new year were passed out and with them the operatives would find out if their wages had been cut because of the new 56-hour rule. No one knew for certain what would happen if the wages were reduced. Strike committees had been set up but no plan of action had been put forth.

The mill owners felt confident that the operatives would not strike simply because they knew the operatives were already living on the edge and could ill-afford to lose any income and put their welfare in jeopardy. But they also felt that if the mill operatives did strike they, the owners, could simply wait them out. This tack had been quite successful in well over 75% of all previous strikes in Massachusetts going back years. Mill owners refused to meet with strikers and hear their demands and usually within a week the workers returned to their position having won nothing. This is where the owners got their confidence.

What the mill owners of Lawrence failed to recognize on that fateful day in January was just how desperate the condition of their operatives was. It is well documented that a full third of all new immigrants who came to Lawrence to work the mills found the poverty of their native land more inviting than the poverty of Lawrence and therefor they returned home. For those who could not go back there was a feeling of “nothing to lose” by going on strike.

Sometime around 11AM in the giant Everett Mill the paymaster walked through the various departments handing out pay envelopes. When he reached one particular room, a Polish woman whose name is lost to history, shouted out “short pay! Short pay!” She promptly left her position and engaged others to do the same. They did. The moved from the third floor, to the second, to the first, gaining followers as they went. They marched out onto the street, Union Street, turned left and headed down towards the other mills, the first being the Duck Mill on their right and the Kunhardt mill on their left.

As they reached the mills numbers of the new strikers stormed through the entrances to these mills and called to their fellows to follow them into strike. They proclaimed that the worst had happened and their action was necessary.

Next they crossed the Merrimack River to the Ayer Mill on their right and the giant Wood Mill on their left where they repeated their actions and gained supporters. At the same time, a splint group from the original had turned right, just before the Duck Mill and marched down Canal Street to the Pemberton, Washington and Pacific Mills. By day’s end thousands of mill operatives were on strike. This was an unforeseen eventuality by the mill owners.