While the character of Sophia in this story is fictional, the setting is based on historical fact. The city in the story is Lawrence Massachusetts. The strike referred to is sometimes called the “Bread and Roses” strike. It was a strike of all of Lawrence’s textile workers from January 11, 1912 to March 15, 1912.

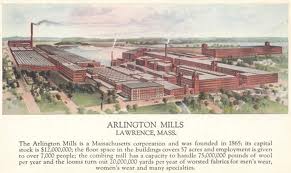

The strike started because worker’s wages were reduced after the state mandated a reduction in the maximum working hours per week of women and children. The hours were reduced from 56 to 54. The worker’s had requested of the mill owners that this reduction in hours would not affect their weekly wage. At the time, the average weekly wage for 56 hours of work was less than $7. That is not an error. It was $7 a week, not $7 a day. Lawrence, known as immigrant city, was basically a single industry town, textiles, with the textile mills employing upwards of 40,000 people, or a little less than half the entire population of the city of Lawrence!

The “old immigrants” of Lawrence, Germans, English, Scot, and French Canadian, were giving way to the new immigrants, primarily Italian and Polish, but also there were Russians, Belgians, Syrians, and Armenians. These new, and unskilled, immigrants provided the largest portion of the textile labor in the city. Their working hours fluctuated greatly, and they never knew from one day to the next if they would be working. Layoffs were extremely common, and when small strikes happened, mill owner usually just replaced the striking workers with other workers. Only 25% of all strikes in America at the time were even marginally successful.

The plight of these workers came into national view when in mid-February over 120 children were sent from Lawrence to New York City where surrogate families had volunteered to take those children who had suffered the greatest. Margaret Sanger, the famed birth-control advocate of the day, had visited Lawrence at the beginning of the strike and was at Grand Central Station in New York to meet the children when they arrived. The socialist movement of New York marched the children down 5th Avenue where all could see. Sanger later commented on the condition of the children they received. Sanger, a trained nurse, claimed all were suffering from severe malnutrition, and many were so poorly dressed that they were not even wearing undergarments. This so incited the American people that a cry went out for a congressional hearing. President Howard Taft’s wife, Helen, urged her husband to take action. The here-to-fore Taft, a friend of industrialists, ordered the House of Representatives to convene an investigation which it did.

At a hearing of that house committee, more than half those interviewed from Lawrence were young people between the ages of 13 and 18. All had worked in the mills and related both their working conditions and living conditions to the members of Congress. At the time the minimum working age in Massachusetts was 14 which also had an education requirement attached. The young people attested that such requirements were easily circumvented by bribing local officials. They stated that their working was an absolute necessity for the survival of their family.

An investigation by the “White Commission” of Lawrence in 1912 revealed that portions of Lawrence were even more densely populated than the most populous portions of New York City, a startling revelation. Those conditions were accompanied by poor sanitation, extremely poor public health measures that resulted in the spread of diseases like dysentery, tuberculosis, and other maladies commonly found among the malnourished.

The strike in Lawrence was revolutionary in that it was the largest strike of a single industry in a single city ever in the United States. At any one time during the two plus months of the strike, as many as 30,000 people were on strike. It became the blueprint for unions on how to run a successful strike in the years to come.

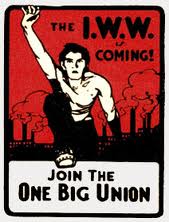

Throughout the strike there was a constant struggle between the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and the American Federation of Labor (AFL) for the hearts and stomachs of the affected. Prior to that strike, however, the AFL had made it quite clear it was only interested in a membership of skilled male textile workers, a fairly small portion of the entire workforce. Conversely, the IWW used their “big tent” format for including all operatives, regardless of job or gender, for inclusion in their membership. At least for the period of the strike, the IWW easily won that battle. However, they were never able to gain even as many as 1000 workers as dues paying members. When the strike ended, the socialist IWW went back into disfavor, and the AFL went back to desiring only skilled labor.

But the IWW succeeded with this strike where most previous strikes had failed. It was unusual in America for any strike to last more than 10 days. Even the largest of strikes, 1000 or more workers, usually ended to the favor of the industrialists. Strikes were frequently violent, particularly when the IWW was involved. The socialist IWW attracted America’s radicals of the day, many of whom were self-declared anarchists. The American memory of that day was still fresh with the assassination of President William McKinley by a professed anarchist. William “Big Bill” Haywood, leader of the IWW, had previously been at the forefront of the Western Mine Workers who had in previous years had a number of violent clashes in Colorado. Haywood had been indicted and tried for the murder of Governor Frank Steunenberg of Idaho. Although Haywood in fact had had nothing to do with the murder, a reputation for violent confrontation followed him the rest of his life. And when he arrived in Lawrence two days after the beginning of that city’s strike, the city fathers feared that violence could not be far off.

The Lawrence strike, however, was not headed by Haywood, but rather by a man who was a poet by trade, and secretary of the IWW office in New York City, Joseph James Ettor. Ettor was a soften spoken, baby-faced man who endeared himself to his audiences. From the start of the Lawrence strike he constantly urged his follower to remain peaceful at all costs. Throughout the entirety of the strike there had not been a single all out riot, although there had been a few confrontations that could easily have descended into an all out riot. Only 3 strikers died by such confrontations, at least one of which was an obvious case of manslaughter at the least, but no one was ever taken to court over these deaths, and the was little investigation done by the police department.

The mill owners, and William M. Wood in particular, head of the huge American Woolen Company which owned six of the mills involved in the strike, felt certain they could wait out the strike without having to make a single concession to the strikers. But in late February when young mothers in Lawrence were arrested and taken to jail, some with babies in their arms, the public attitude towards the strikers changed markedly. It become more and more apparent that the industrialists claims that the strike was a movement by a subversive and un-American element, was simply a falsehood. But even more, merchants whose livelihood depended upon the business the strikers brought them was impacted. A solution had to be found.

All the powers of Massachusetts, Governor Eugene Foss, Senator Calvin Coolidge, Cardinal O’Connell, who had adamantly opposed the strike at its beginning, moved for a quick reconciliation by the time March rolled around. The conditions over the average worker had been spelled out in great detail by newspapers like the Boston Globe and the New York Times, and the industrialists found themselves in a no-win situation.

When the strike ended on March 15, four of the five demands made by the strikers were met in full. They had demanded, and gotten, a 15% pay raise. But even more importantly, they had shown the world how to conduct a successful, and peaceful, strike. A few days after the end of the Lawrence strike, the textile mills of Lowell Massachusetts, who employed equally as many people as did Lawrence, went on strike. That strike was settled relatively quickly. A year later the silk industry of Paterson New Jersey, a fairly large industry at the time, went on strike and it too used Lawrence’s methods to a successful conclusion.

What most importantly came out of the Lawrence strike was first the living conditions of the average mill operative in American cities.

Images such as those above were printed in newspapers across the United States. The federal government realized that state laws protecting children were largely ineffective, ambiguous, or non-existent. A minimum working age of 12 was common in the southern states while pictures such as those above belied that such laws were being followed.

The federal government, in the several years following the Lawrence strike, enacted a series of child-labor laws, minimum wage laws, and even a few laws governing working conditions, although these laws stayed very weak until the 1950s.

The location of “Sophia” in my story was on Common Street in Lawrence. On a single block there were a good number of three and four story tenaments which housed anywhere from 50 to 80 people in a single building! Although such building generally housed a single ethnic group, it was common that a house full of Poles would be neighbor to a house of Italian or Armenians or some of the older, yet equally poor, Irish and English. The plight of these workers is detailed in works such as “Huddle Fever” by Jeanne Schinto, “Twenty Years at Hull House” by Jane Addams, and in the case of Lawrence, “Bread and Roses: Mills, Migrants, and he Struggle for the American Dream” by Bruce Watson.