I grew up in the town of North Andover Massachusetts. North Andover is a small town some 25 miles north of Boston, and borders the cities of Lawrence and Haverhill. North Andover in the 1950s and 1960s was a quiet town, a town whose history was steeped in the revolution, and which had its share of Massachusetts blue bloods. Still, it was a mostly middle class town, a small number of wealthy families and a small number of poor families. It had in those years only just begun to inherit the 2nd generation immigrants from Lawrence, mostly Italians and Poles. They were the children of new immigrants who had escaped the textile mills of Lawrence and its tenements to the single family homes of North Andover. A few still worked the mills, one of which, Stevens Mill, was a textile mill located in North Andover.

In the 1950s North Andover still had a handful of working farms, several of which were cow farms, and one turkey farm. For that, the residents of neighboring Andover derisively nicknamed North Andover “Turkey Town.” Andover was home to the elite Phillips Academy which had produced presidents, senators, and many wealthy businessmen. Andoverites never missed a chance to assure the people of North Andover that they lived in a town that was something less than Andover, a poor relation. It didn’t affect us in the least.

The part of town I grew up in, known as the “old centre,” was mostly made up of upper middle class families. It was not an area where, for the most part, young families lived unless you were part of the town’s old families which we were. Our house was one of the homes which lined the town common, a large and old green area situated next to the North Parish Church, the first church of old Andover, and founded in 1646. All the original families of the town belonged to the North Parish Church, and my family was one such, although that was only my father as my mother was Roman Catholic. Things were changing. The picture below is of the North Parish Church as seen from the common.

We were sheltered from the greater world. The city of Lawrence, with its many ethnic neighborhoods, had a very stable population whose newest members were from Puerto Rico, a sign of things to come but not anything anyone took any particular note of. If there were black families in Lawrence, I never saw them and was entirely unaware of them. The first black man I ever set eyes on came in my sophomore year at North Andover High School, 1963, and he was an exchange student the North Parish Church had brought from Africa. He was the last black person I knew prior to my going to school in New Jersey in September 1965. Even my trips to Boston with my father on his business trips did not impress upon me the presence of the black population that lived there. And that’s how it was.

Although there was some joking about a person’s ethnic background, none of that was ever taken seriously. No one seemed to truly care what a person’s ethnic background was. If there was bigotry in the town, it was well hidden. We did not learn, nor was anyone trying to teach us, any sort of racial or ethnic bias. Maybe things would have been different if there were some black families living in the town, but there were not.

My family was what was referred to as being “land poor.” It meant we owned lots of land but did not have much money to go with it. I never wanted for anything but I never got an allowance. I did not even know such a thing existed, quite honestly, so asking for an allowance was alien to me. It was expected that I would mow the lawn, rake the leaves, and take out the trash, and shovel snow in the winter, all without compensation of any sort. I actually enjoyed and took pride in such chores, and so I always did them willingly. It was what was expected of me, and I thought that was a common thing that members of any family were expected to do. Then one day, I was not more than 6 or 7 years old, the boy who lived next door said we could earn 25 cents if we shoveled this lady’s driveway. I had never heard of such a thing! Earn money for shoveling snow, incredible. That was my introduction to earning money, and from then on I was always thinking of ways to earn money. Her driveway was less than a third in length of my own driveway which made the job all the more desirable.

In my late adolescent years I had a paper route. I delivered the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune to some 60 customers. The price of the paper was 7 cents a day, and 42 cent the week. Strangely, getting a tip meant the customer gave me 50 cents a week. But who gave me such a tip was inversely proportional to their income. The rich waited at the door for their 8 cents change after giving me 50 cents, while the poorer customers never thought to do such a thing. I also managed a burgeoning lawn mowing business around the neighborhood. My main customer was the same lady who wanted her driveway shoveled in the winter. I could get all of 2 dollars for a simple mowing! I never wanted for money and always had enough to go to the movies in Lawrence at the Palace and Warner movie houses, theaters of the old single screen variety, now long gone.

When I turned 14 I somehow learned of a summer job at Calzetta’s Farm. It was regular work with a regular wage. My lawn mowing business was a bit irregular, some of my customers given to occasionally mowing their own lawns in spite of my services offered. The farm job required my presence from 8 in the morning until 5 in the afternoon, five days a week for the handsome sum of $15 a week. I thought I was rich! In the early summer we picked strawberries, weeded the fields, and did whatever the farmers, the brothers Tom and John Calzetta, demanded of us. Two other young workers, both from the Essex Agricultural Institute, worked with me. Farm work then, as now, did not suffer a minimum wage requirement, hence the acceptable level of pay we received. As the name shows, the Calzettas were Italian immigrants, though Tommy and John were second generation. But everyone regardless of age who lived on the farm, worked on the farm. The 80 year-old grandmother, dressed in her black mourning garments, worked the 90 degree fields the entire day with the rest of us. It was hard and dirty work, and when I got home I always had to take a bath. I worked that farm for two summers, my second I received the wage of $25 a week, I knew I was at the top of my field! The thought, however, that I was possibly underpaid never once crossed my mind. I always had money in my pocket and that was what was truly important to me.

The next summer, after I had turned 16, I did not want to go back to work on the farm. It was too much work! There was a man, a wealthy man we all knew, who lived in a new house on the common not far from my house. It was the only modern design house, a ranch, which was ever allowed to be so constructed around the otherwise colonial area around the common. I knew he owned a mill in Lawrence, and so I literally knocked on his door one evening and asked for a job in his mill. I do not remember how the conversation went, but he told me to meet him the next morning at 6:30 and he would take me to the mill.

His name was Segal and the mill he owned was known as Service Heel Company, maker of heels for women’s shoes. That morning was the last time I ever saw Mr. Segal. He took me to the mill’s office and directed someone to give me a job, after which he disappeared into his own office. This was the beginning of a most important part of my education, unbeknownst to me of course. After that morning, I caught the city bus, which stopped right next to Mr. Segal’s house, each morning, lunch bag in hand and ready, more or less, for the day ahead. My pay was the minimum wage for 1966, $1.25 an hour. That was $10 a day and $50 a week. I had doubled my income over the previous summer! But I was warned, upon taking the job, that I had to be on time which meant being clocked-in by getting my time card stamped by 7AM, otherwise I would be docked 6 minutes if I were even 1 minute late. I was paid entirely according to my time card. And if I were late, I could not make up that time at the other end of the day without permission, and such permission was never given. The picture below is of the mill I worked in. In the foreground is where the Puerto Ricans worked, and in the background was where I worked. Although it is not obvious, these two structures were not connected.

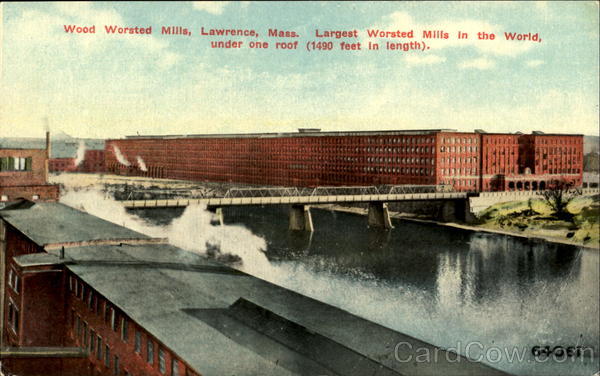

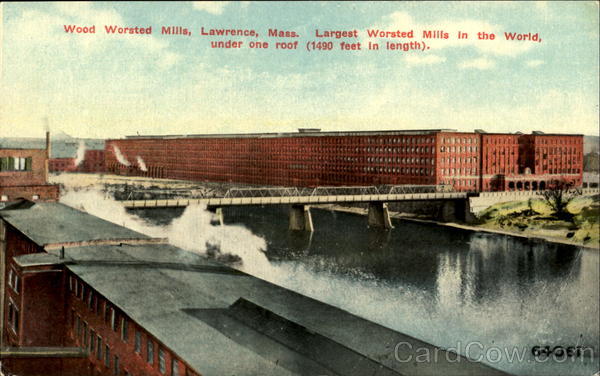

Service Heel Company was located in the old George F. Kunhardt textile factory. By 1966 the once booming textile industry had entirely abandoned Lawrence, and a considerably smaller shoe industry had taken its place. Still, at the time, Lawrence was second only to St. Louis in the production of shoes. But that did not last. Most of Lawrence’s vast textile mills stood vacant, relics of a bygone era. The textile jobs had left but the people had not. Many of the workers at the heel company had previously worked the textile mill at that very location. One woman related to me that she had worked in that mill for over 35 years doing piece work the entire time. At the time, piece work was exempt from the minimum wage. I could not imagine sitting in such a place for so long a time doing basically the same job for all those years. But she never complained. To the contrary, she, and most of her fellow employees, always seemed grateful for the work they had. There was not any sense of entitlement among these people. Below is a picture of some of the textile mills of Lawrence.

In 1966, the Lawrence mills were segregated, not between black and white, for as I said there was no black population, but between Hispanic and everyone else. That fact was brought to my attention by the foreman, a very large and smelly man named Tony, who took me to the far side of the mill and pointing to the mill next door said, “that’s where the spics work. You don’t have anything to do with them.” He was referring to the Hispanics who worked that mill. And his statement, rather than being a suggestion, came across as a command. But I knew in my heart that there was something inherently wrong with his statement, although I doubt I could have explained why I felt that way. The heel workers were almost entirely of French and Italian ancestry, and as such, were the old immigrants as opposed to the new immigrant from Puerto Rico. But my experiences in Lawrence at that time never included any feelings of fear or animosity towards the Puerto Ricans aside from what Tony had pronounced. But I did not challenge his belief either, after all, he was my boss and in charge of my continued employment.

I was a “floor boy” in the mill. I was indoctrinated into the erstwhile sweatshop. No air conditioning, no break room, no fans, no drinking fountain, only the steady clanging of machines and the smell of paint and glue as was applied to the heels. The heels were placed by their type into wooden boxes, about a bushel in size. It was my job to move the boxes from where they were “made up,” that is, the box had a particular type of heel put in them, to the proper station of the worker who would either cover the heel with leather, paint the heel, or press a nail into the heel. Each job had a color coded ticket in it to signal when it was due to be finished. I caught hell any time I moved the boxes in the wrong order or took them to the wrong station. It was only Tony who gave me hell, as the worker at the station involved was inclined to giving me a friendly nudge to say I had messed up, but that I should not worry. These were the people who were rightfully referred to as “the salt of the earth.” They were kind hard-working people who you ate lunch with, got to know, and counted on to help you along. They were union people who warned me that at the end of working 90 days at the mill I would have to join the union, but the cautioned me against that, not because they disliked the union, but because they knew I was still in school and wanted me to continue my schooling so I would not end up where they were. But it was this very sort of worker who moved his family to North Andover to help their children get a chance at a better life.

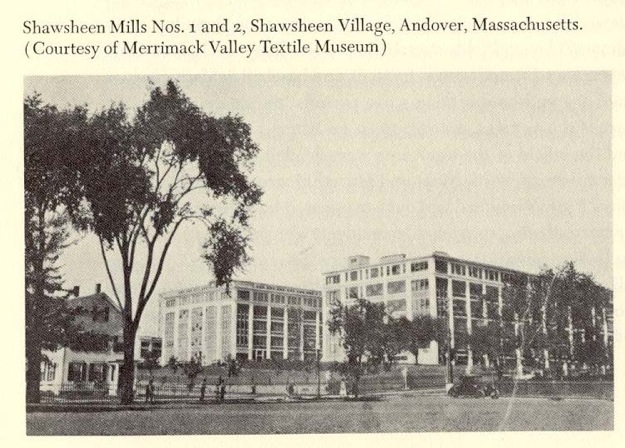

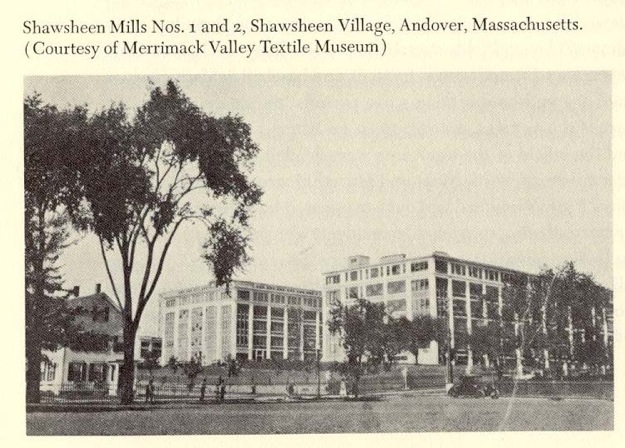

The next summer I worked for the Raytheon Company at its facility in Shawsheen Massachusetts, its “missile systems division.” I got that job because my best friend’s father worked there and said he could get me some sort of job working there. I was a “clerk” whose main job was finding and filing schematics for the technicians and engineers who worked in the department. I found out that summer two thing, first, I received 10 cents an hour more than a woman who held the exact same job and started exactly when I did. I got that 10 cents because I was a man. I also first heard the word “scab” as it was used to connote someone who crossed a picket line during a strike. At the end of the summer Raytheon offered to pay for my college education if I remained there and took up a career in electronics. But the job had left a bad taste in my mouth and I turned them down. I had tasted gender discrimination and knew I did not like it. I also acquired a negative feeling for unions, but that was due to my ignorance, and was something I later replaced with knowledge and a healthy respect for unions and their membership. Below is a picture of the old Raytheon Mills in Shawsheen. These mills were a part of a failed textile mill experiment.

That fall I entered Boston University, where I did incredibly poorly, and dropped out shortly before the end of the semester in December 1967. I took a job pumping gas at a local chain gasoline dealer, pumping Texaco in North Andover, Andover, and Lawrence. But that job I knew to be temporary as I had my sights set on going to the US Army’s aviation school. And on February 19, 1968 I was sworn into the US Army and on the following day flown to Ft. Polk Louisiana. Still, the job gave me work experience in yet another area. In those days there was no such thing as pump your own gas, and almost every service station pumped your gas, cleaned your windshield, and checked your engine’s oil level. Regular gasoline ranged from 28 to 32 cents a gallon in those days, oil was 40 to 50 cents a quart.

I had never been out of the northeast prior to going to Ft. Polk, and I was in for an education unlike any I had thus far known. My last two years of high school were spent in Bordentown New Jersey where a number of my classmates were black or Hispanic. But because of my father, my upbringing in his Unitarian culture, it never occurred to me that their heritage mattered. We were just guys who were all intent on doing the same thing. My trip to Ft. Polk was about to present to me a type of prejudice I had not known.

The trip to Louisiana involved flying to New Orleans followed by a second short flight to Lake Charles Louisiana. From Lake Charles I had to take a bus to complete the journey to Leesville Louisiana where Fort Polk was located. I remember staring out the bus window at the southern streets as they passed by, and at one particularly memorable stop, I saw the peculiar sight, to me at least, of two water fountains right next to each other on the outside of a building. Above one was the sign “white” and above the other “colored.” I was educated as to the ways of the “old south” which had yet to give way to a new way of thinking.

The US Army in 1968 was heavily engaged in the war in Vietnam, and it quite literally did not have time for anyone’s prejudices. I would say roughly a third of the men in the company I was assigned to were black. But to me, and to the army, they were just one of many, who had one job and one focus. Anything that was not related to our being properly trained as a soldier was not approved of. The assimilation of all races in the military was nearly complete and the vast majority of men in the army were forced to leave behind them whatever prejudices they had brought with them. The picture below is what my company area looked like in 1968.

The most telling time in those early months of my military career came on April 4, 1968 when Martin Luther King was assassinated. In the bunk next to mine was a black man who upon hearing the news of Dr. King’s assassination broke down and cried. I did not then understand the importance of the man. All I knew was what the northern media, and the government, wanted me to know about Dr. King, and that was all negative. It was a hard lesson I had to learn, but learn it I did. That day, and several days afterwards, it was reported that there were riots in Leesville and many other locales. The post was closed and we were denied day passes to leave the fort.

That was my experience up to 1968. It was not particularly unique except that it was mine. Others experienced many of the same things, just in different ways. The 1960s changed me in more ways than I was aware of at the time, but am the better for now.